Clair Wills has written a fascinating and insightful book about the role of immigrants in Britain between 1940s and 1960s. Popular history and culture frames post war migration around the images of the West Indian community and the “Windrush generation,” but this is far from the complete story as Clair reminds us that Poles, Latvians, Lithuanians, Ukranians, Italians, Maltese, Cypriots, Indians, Pakistanis and the Irish made up this multi-cultural group. And for me, the daughter of Irish migrants, the book’s recognition that the Irish were the biggest group – 40,000 per year in the 1950s- is an important addition to the history of immigrants in this country.

She dispels the myth that Britain welcomed them for unselfish reasons. “…in the end, however, the needs of the refugees were neither here nor there besides the needs of the countries offering refuge.” The newcomers provided the labour needed to rebuild the post war economy; jobs that were often low paid, unskilled and manual.

One key fact was that, until the passing of the Commonwealth Immigration Act in 1962, over a quarter of the population of the planet – reflecting the reach of British Empire – had the right to come and live in Britain as citizens.

Jamaican migrants welcomed on Windrush

Lovers and Strangers is quite different from most mainstream histories of post war Britain because, as Clair says; “I have tried to narrate the the history of migrants’ and refugees encounters with Britain through the experience of migrants themselves, and through contemporary accounts of that experience: contemporary interviews, articles and letters in the local and community press;manifestos; short stories;autobiographies;political essays; as well as oral poetry and folk songs ranging from Irish ballads to Trinadadian calypso, Punjabi qisse and bhangra lyrics.” Or not just how the newcomers looked to the British but how the British looked to them.

For West Indians coming to Britain, unlike other migrants, they believed they were coming to the Mother Country. Clair quotes writer and Trinidadian George Lamming. “England lay before us, not as a place or a people , but as a promise and an expectation.”

One group that has been largely forgotten in the history of post war immigration is the displaced people who were victims of the post war carve up of Europe between the allies. Over 85,000 came to Britain. the British, like most of the Allies, were not particularly principled in their dealings with traumatised groups, including Ukranians, Yugoslavs, and Baltic people, allowing in those that they thought would be useful, rather than those in most need of help. . As Clair points out, ”It is uncomfortable to dwell on the assumptions about class and breeding which lay behind the processes by which they were chosen – so Baltic women, ‘of the same racial background to us’ were taken in preference to Jews.” Again it was a story of solving Britain’s labour shortage, rather than alleviating the refugee problem.

One of the great strengths of the book is this looking in at British society, but for me one of its big failings, particularly when documenting the lives of the Irish in Britain, is the absence of an anti-imperialist viewpoint.

You cannot talk about the Irish in Britain without talking about the British in Ireland and the fact that Ireland was Britain’s first colony. For centuries the Irish moved in and out of Britain, not just to work but to take part in the struggle for the independence of Ireland.

Missing is any reference to the work done by groups such as the Connolly Association, a group of Irish born and second generation people who had links to the Communist Party. During this period from the 1940s-60s the Connolly Association almost singlehandedly raised the issue of the discrimination faced by Catholics in the North of Ireland, as well as that faced by Irish workers in Britain.

Though Clair does mention the Connolly Association newspaper The Irish Democrat and its interviews with Irish nurses and discrimination, she fails to include the role played by the CA in consistently raising political issues and fostering the Campaign for Democacy in Ulster in which Manchester MP Paul Rose played a leading role. Instead of acknowledging this, Clair makes reference to activists such as Eamonn McCann and fringe groups such Irish Communist Group and Irish Workers Group, who had minimal influence in Britain. She mentions Brendan and Dominic Behan as playwrights and singers, but not their brother Brian’s activity in leading one of the biggest building workers strike in the 1960s.

Irish writer Donall McAmhlaigh, whom she quotes extensively from his novels and writings about his life as a manual worker, was a member of the Connolly Association and wrote for The Irish Democrat. I think he would be upset to know that the political nature of his writings had been reduced to social history.

Donall

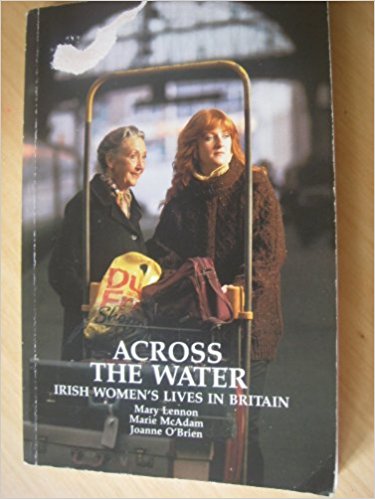

Clair weaves in her own history into the narrative, and this makes for powerful story telling. In 1948 Clair’s mother made the journey from Cork to join her older sister to work in a psychiatric hospital. Irish women have a key role in the story of emigration which I feel Clair fails to fully acknowledge. In Across the Water, Irish Women’s Lives in Britain” (1988) the authors Mary Lennon, Marie McAdam and Joanne O’Brien documented the fact that at various times over the last century more Irish women than Irish men have come to live in Britain and that their experiences have been largely ignored. They firmly locate the Irish and women in a political context, and specifically giving space to women who were activists in their trade union and political organisations.

Lovers and Strangers is a well written and accessible social history book. We get an insider’s view of what living in Britain was like for a very diverse group of newcomers. Post war British society was changed by the new immigrants, and continues to change in ways that for many of us in 2017 we do not even notice. And whilst Clair does ensure that her community, the Irish, are given a significant role in the story, it is one that I feel is not fully given its true historical context.

Brexit is the latest challenge to the notion of what it means to be British. Nowadays it is the thousands of EU citizens who have lived in this country for many years who are having to decide whether to stay or go. And once again the Irish and their descendants are caught up in the real politics of Britain’s role in the North of Ireland. For many Irish descendants who never thought about themselves as Irish are now rushing to get Irish passports to stop themselves being locked out of the EU, rather than as an assertion of Irish identity.

Unfortunately Lovers & Strangers costs £25. If you can buy it here

Reblogged this on Anarchy by the Sea!.

Thanks – a very interesting review. I will buy the book.Been involved in anti racist campaigning most of my adult lifeand want to learn more.Currently reading Fruit of the Lemon – A Levy.

From: lipstick socialist To: derbypeoplesh@yahoo.co.uk Sent: Sunday, 27 August 2017, 10:06 Subject: [New post] My review of Lovers & Strangers An Immigrant History of Post-War Britain Clair Wills #yiv6348034528 a:hover {color:red;}#yiv6348034528 a {text-decoration:none;color:#0088cc;}#yiv6348034528 a.yiv6348034528primaryactionlink:link, #yiv6348034528 a.yiv6348034528primaryactionlink:visited {background-color:#2585B2;color:#fff;}#yiv6348034528 a.yiv6348034528primaryactionlink:hover, #yiv6348034528 a.yiv6348034528primaryactionlink:active {background-color:#11729E;color:#fff;}#yiv6348034528 WordPress.com | lipstick socialist posted: ” Clair Wills has written a fascinating and insightful book about the role of immigrants in Britain between 1940s and 1960s. Popular history and culture frames post war migration around the images of the West Indian community and” | |