Alice

In 1953 the Communist Party published a booklet called “Five Women tell their story” which told the story of five working class women who joined the party to change the world. But one of them was not new to the CP; Alice Bates had been a member of the party for over 10 years. This is her story.

Alice Bates, (nee Toal, was born in Manchester. (The name Toal was a derivation of the Irish name “O’Toole”). Her father David from a Protestant family while her mother Sarah was from a Catholic one. Unusually they married in Christ Church, Acton Square, Salford, a fervently Protestant church.

David was a coal hawker, selling coal around the area. Sarah worked in a cotton factory before she married. Over 18 years she had six children; Alice was the last, born in 1920.

Alice says she grew up in a “strict Catholic family,” attending St. Edwards’ Primary School, followed by a convent school. It is a mystery how the family went from her parents being married in a Protestant church (a virulently anti-Catholic one at that) to the children being been baptised as Catholics and attending Catholic schools.

She grew up in Hulme and says that when she was four years old the family moved to a new housing estate and “My horizons were opened up… I was the one who was looked to, to make something for the family.” She went on to the Catholic convent school and then passed the entrance exam and obtained a job in Manchester City Council.

Alice’s politics were shaped by her own experiences and what she saw and heard around her. At her Catholic school in the 1930s support for Franco against the Spanish Republican parties was preached: she wanted to find out more.

But at the local Platt Fields Park she could hear other voices and other opinions. “I began to read more and on Sunday afternoons listened to the speakers. I listened closely and wanted to find out more.” Alice became interested in the Labour League of Youth – the young socialists of the Labour Party. In the 1930s they had a strong branch in Manchester and were close to the Young Communist League.

Alice was now working for Manchester City Council in the Public Assistance Office who paid out benefits to poor people. Alice’s father had been out of work for many years and the family lived on a low income and had to go to the office for support. “At first, I was so ashamed of my family’s poverty that I never told my work-mates anything about my family, and never asked them home. But after a while I felt a great sense of injustice that while thousands of families like ours were just existing from week to week, hundreds of others (according to society gossip) were able to spend more on one meal or one coat than we had for a whole week.”

In 1938/9 she went to meetings and discussions and in 1940 decided to join the Young Communist League and soon became District Treasurer. There Alice met her husband Norman and married him in 1942. They joined the Communist Party together. “I joined the Communist Party, because I felt that here was a party that not only understood how families like mine had to live, but saw what must be done to alter things — not just in the dim and distant future, but practical things that could be done almost from week to week.”

Her job as a civil servant was in a reserved occupation but Alice wanted to become involved in the war effort and industrial production so she went to work at Reynolds making chains for anchors. As an engineer Norman was also in a reserved occupation.

The trade union in the factory was very active. “Everyone was in the union and the big fight politically was for a second front to be opened. I was involved in calling for this at meetings and taking around petitions.”

In 1944 she had her first baby at home. Returning to work part-time her mother looked after the baby. At this time there was a demand for nurseries so that women could return to work. Alice went around her local area asking women to sign petitions for nurseries. Eventually one was opened at the end of her road – a day nursery – open 8am – 6pm. It cost 15s per week and the staff were all trained.

Post-war the Government wanted to close the nurseries. Alice set up a local Housewives Group which collected petitions outside nurseries and campaigned to prevent an increase in prices i.e. children’s clothes and shoes and basic foods. “We had very little success. We went to our local (Tory) MP and he treated us with contempt as if we had right to raise the issue.”

One of the big issues for families was that family allowance was only paid to the second child and one of their demands was that it should be extended to the first child. “Our MP eventually raised it and it was brought in. We felt we had made an impression on him.”

Another issue they took up was that conscription continued after the war but if a young man married under the age of 21 the wife did not get an allowance. They raised this and eventually it was brought in.

Selling the CP’s paper the Daily Worker (which became the Morning Star in the 1960s) was an essential activity for Alice throughout the 1940s and 1950s. “The majority of our members came through reading the paper. We would sell 200-300 copies in a morning at various places from factory gates to door-to-door.” It was an activity she continued all her life.

Britain’s involvement in the war in Korea was also a big issue for the CP, and Alice. “In 1956 the push for power in the far east led us onto the streets to show our opposition to the war – and Britain’s involvement.”

Alice organised a street meeting in Miles Platting in Manchester. This was after a local young man had been killed in action. “I stood on a stool and started talking about CP policy on the war in Korea. The family (of the young man) and their neighbours were very hostile. We were moved off by the locals – physically lifted us up and moved us on – but we stuck to it. I did three meetings in that area. They were not so hostile after a while. I think it was important that a woman spoke and it certainly brought the women out of the houses to listen.”

By the 1950s Alice was a women’s full-time organiser in Lancashire for the CP. Her work involved setting up branches and speaking at public meetings for the party. “I would go into shopping centres and hold meetings.” She concentrated on organising housewives as they were out of work, not part of a trade union, and living on low wages. “Women knew the problems of prices and nurseries and my aim was to get them to play a bigger part in the movement and to reorganise trade unions so they could take part.”

But she makes an important point. “Not separately from the men because we were speaking as part of the whole movement. But we were bringing forward the particular demands of the women to be settled in order that women could play a greater role in the community. Part of the demand was for different types of unions in the Trade Union movement .“

Celebrating International Women’s Day became a key part of their activity, creating a focus for women to meet up and articulate their demands. The Women’s Parliament was set up by several groups including the Communist Party, the Labour Party, trade unions and housewives’ groups. Its aim was to get women delegates from all these organisations and to have an assembly: a parliament for women.

In the mid-1950s a National Assembly of Women was held in the Free Trade Hall, Manchester and several hundred women took part. “The issues discussed included prices, nurseries for women to go to work and the need for peace” and “showed women who felt they could not do anything their own strength.”

By this time Alice and Norman had three children. Norman was on strike for higher wages and Alice, with baby in arms, joined him and spoke on the picket line in support of the men. “It was important to show the wives were behind the menfolk and show solidarity.”

In 1947 Alice stood as a Communist Party candidate locally. She only gained 132 votes but she felt it was important to get CP candidates on the local council. They were one of the first parties in the area to have a female candidate.

Alice said that working with women she never felt separate from the rest of the movement. “Everything I was working for, even the issues that directly related to women including lower prices were all linked toward socialism for me – they were never separate.”

She said her job as a women’s organiser was to get women involved in the party and the movement. “Many of them registered as party members and branches were 50/50 women/men. But women only considered themselves as silent partners. ‘Only housewives’ they would say. It was important to get these silent women to come out and speak about these things and then to take the step of actually doing something.”

Alice continued to develop her own life. At the age of 40 she qualified as a teacher and was an activist in her trade union the National Union of Teachers for most of her working life, 1964-80. In the 1970s she was NUT Chair and Teacher representative on Stretford Education Committee .

She also worked all her life for peace in the world, setting up a CND branch in her local area Stretford.

The 1960s saw the second wave of feminism start up with the new Women’s Liberation Movement. This challenged not just women’s role in society but the family – raising issues regarding sexuality and identity – and challenging the policies of mainstream parties such as the Communist Party.

Alice interpreted this movement as one that was anti-men. “I had worked for years with men in the CP as an equal. And I’d never thought of myself as anything but an equal in the CP, whether I sat on a committee or just stayed at home and looked after the children. I was equal and I’d always considered that. I didn’t think I’d I have to go out and burn my bra to tell people I was equal!. My husband and I always had that kind of relationship. To me every housewife who was working for social issues and helping her neighbours in her own area, she didn’t have to prove her equality with the other men. It was there. And when you sat on a committee you were there. To raise these issues over and above what I considered basic working-class issues of equal pay, of conditions at work for women – those were the kind of things – the question of nurseries , the question of time off when your baby was born, the allowance for women to have children and still go out to work, had always been fundamental to me. “

It was an era where the CP was now a much smaller and less influential party. Women like Alice were now less likely to join and if they did there was not the grassroots movement. She saw this change as academics dominated the party. “To be able to talk about working class conditions and do it eloquently is a very good thing. To be able to analyse the class struggle is necessary. But to experience the class struggle at the sharp end is another thing, isn’t it?”

Over the years Alice held many roles in the party: District Committee member, District Women’s Organiser, ranch chairperson and branch secretary, and Executive Member.

Like other women of her generation for Alice the CP was a magnet for her and her working -class background. It spoke to her views of the world, her experiences of that world and her hopes for a better future, a better world for all. “And we’re still talking about them- about nurseries and parental leave and so on – to me those have always been fundamental things, but they have never taken the place of the basic class struggle on wages, conditions, employment, and peace.”

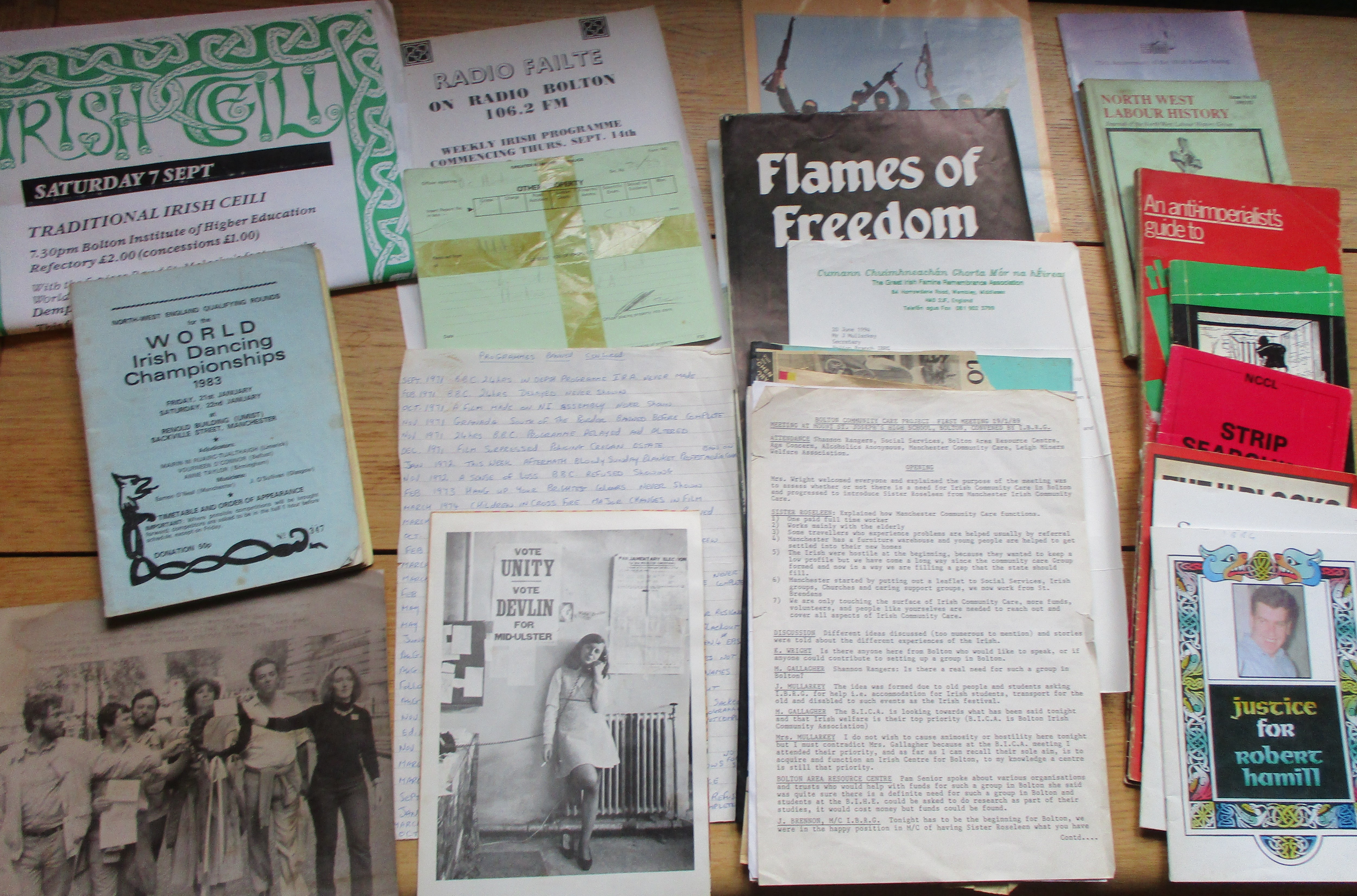

Alice’s archive is held at the WCML.https://wcml.org.uk/