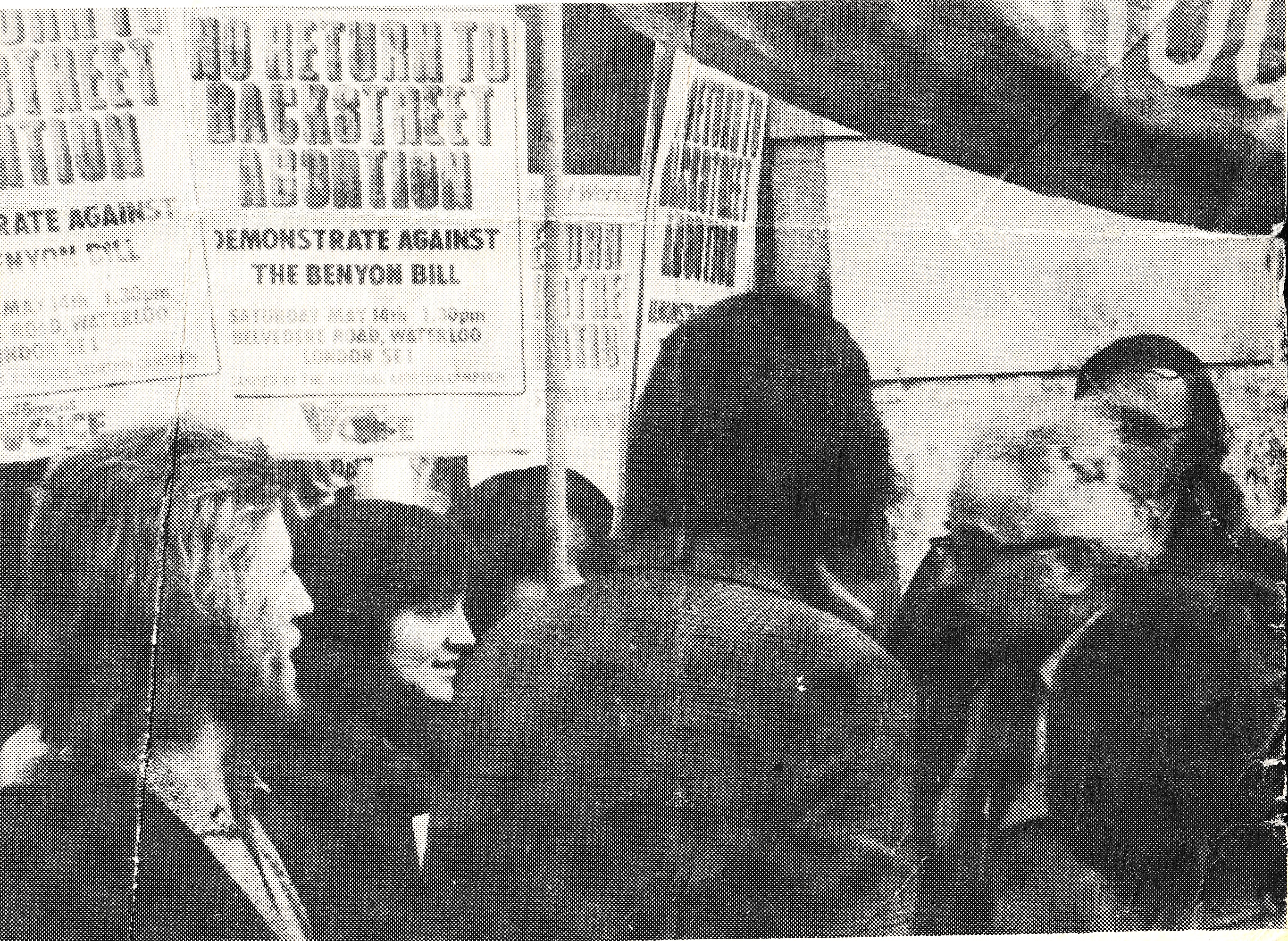

This is a picture of me in 1977 picketing Hull Irish Catholic MP Kevin McNamara’s surgery alongside other women and men in the local National Abortion Campaign branch. Later, he was as useless for the Irish community in Britain as he was for women. Returning to my Irish Mancunian and Catholic working- class family I did not get the response I expected.

When I returned home proudly wearing my NAC badge to my amazement my parents told me they supported abortion because they had seen so many terrible things happen to women in Ireland. They were also probably secretly happy that I was not involved in Irish politics… but that would come later.

My politics were shaped by those of my family. Overtly by my dad’s (Patrick) Republican and socialist ones, and covertly by my mother’s (Betty) more subliminal ones of “don’t get married,” “make sure you earn your own money – and keep it!” They were part of the generation that had escaped Ireland after the Second World War and were wanted over here for their labour – but not otherwise valued.

My mum told me she was free here, she had been able to live with her friends, get a job (and be paid) and was able to do what she wanted outside of work hours. She probably did have more freedom than most of the working -class women she worked with.

Getting married changed all that for her; but like many families we benefited from the post war Welfare State. I represented that “advancement” when I got a place at university in 1976.

But as I grew up, I became aware of the real world my parents inhabited. Around us in Manchester in the 1970s Irish homes were being raided by the police, innocent political activists such as the Gillespie sisters were framed and sent to prison and the Irish community retreated from voicing their views about Britain’s continuing colonial presence in the North of Ireland.

During the summer holidays I went to work at the local factory where my mother worked part time. For the first time I heard people making anti-Irish comments. When I told the women I worked with that I was making money to go to Ireland to see my family there they were horrified. They told me I would be blown up because that is what happened to English people who went to Ireland. I suddenly realised what my mother must have been experiencing as she had an Irish accent., though I do not think I talked to her about it.

Later, I found out that Irish women experienced racism differently from men. My father worked (or rather was exploited) by an Irish firm with mainly Irish workers but Irish women, like my mum, were vulnerable after an IRA bombing, and might be abused verbally or as happened to a friend’s mother, might be refused service in a shop.

Working in Liverpool in 1982 it was through my involvement in my union, National Association of Local Government Officers, that I came across women who were pushing for better terms and conditions for women members: not just equal pay but negotiating time off for women to have a raft of health checks.

Over the years I have been a trade union activist and been inspired by and written about many women from history, who were active in the trade union and labour movement.

In 1985 I was living in Bolton and came across a branch of the Irish in Britain Representation Group. IBRG was a group of working-class women and men who were part of a grassroots, national organisation that had been set up 1981 to raise the issue of Britain’s colonial role in the north of Ireland; campaign against anti-Irish racism and discrimination; and promote Irish culture, history, and language.

IBRG reflected not just a more politicised generation of Irish born in this country, but an organisation that was 50/50 women and men. From 1981-2003 there was a female president (Maire O’Shea), two female chairs (Bernadette Hyland and Virginia Moyles) as well a Women’s Subcommittee, a Women’s Officer, IBRG women’s meetings, while in common to many radical organisations at that time, crèches were provided for all national meetings.

IBRG was an organisation that ensured that it took up issues affecting women in Britain and Ireland. This included sisters in Britain taking up issues including strip searching, divorce, abortion, and contraception.

Women and progressive men dominated the organisation and few arguments took place at meetings around these issues. But in my branch in Manchester a group of reactionary men had dominated the organisation until I joined in 1986.

Moving the meetings away from a Catholic club which was not easy for women to get to (or want to get to) and recruiting women drove these men out. Our branch had women with children, working class women as well as students and professionals such as myself.

The sexism came from the traditional Irish community organisations; particularly from (and well named!) the Council of Irish Associations – the CIA. They tried to get our women’s day excluded from the council-run Manchester Irish Festival as well as an event on the Birmingham 6 campaign.

The Council was run by a left -wing Labour group that had adopted many progressive policies on Ireland due to the activity of the Labour Committee on Ireland locally and nationally.

The Council made sure we were involved in all the events and initiatives that they rolled out to the Irish community. They also took up the issue of anti-Irish racism and were prepared to challenge organisations that included Irish jokes or slurs in their material.

IBRG, like many community- based organisations, offered experience and opportunity to women to become active on many issues. Working-class women benefited the most because it gave them the confidence to change their lives which also meant they changed society. Today, those women are absent from many organisations and society is poorer because of it.

The history of the IBRG can be accessed at the Working Class Movement Library see https://www.wcml.org.uk/ or on my website Lipstick Socialist https://lipsticksocialist.wordpress.com/

Eye opening,Bernadette.Need to read it a couple of more times.Laraine