There is something strange going on when plays about trade union defeats (including We are the Lions, Mr Manager about Grunwick and We’re Not Going Back and Shafted about the Miners’ Strike) have never been so popular, whilst actual trade union membership is on the decline. Trade union membership has halved from a high of 13.2 million in 1979 to 6.2 million in 2016.

In this new book on South Asian women’s involvement in struggles for equality at work, the authors show that there is a history of over four decades of South Asian women taking part in labour struggles in the UK. They place that activity within a broader context; one that takes into account how and why the women came to the UK; and how the connections of race, ethnicity, gender and class thrust them into their roles as women who resisted oppression at work and took their activity onto the streets.

The authors challenge some of the myths around the Grunwick strike; “the celebration of the strike increasingly resembles a kind of political nostalgia, a longing backward glance to the muscular activism of mass picketing, confrontation with the police and a centrifugal drawing together of all the progressive elements in the labour movement and the wider left.” Instead they show the forces lined up against black and ethnic minority workers: how they were not just fighting discrimination by employers, but also from fellow white workers – and even trade unions.

Grunwick picket line

This book documents this history, and shows how black and ethnic workers, together with their communities, challenged discrimination. In 1963 a local community group, the West Indian Development Community in Bristol, challenged a local bus company that refused to employ black and Asian people as bus crew, a policy that was supported by the white workforce, and shockingly by the trade unions. Following the example of black people in the USA at that time the local community boycotted the bus company, and through a national campaign, forced the company to lift the ban on non-white workers.

Bristol Bus Boycott

Lobbying by trade union members to challenge discriminatory practices within the trade union movement led finally in the late 1970s and early 1980s to a recognition that racial discrimination needed to be challenged , and that black and ethnic minority workers needed to be incorporated into the trade union movement.

But what was, and is, the reality for black and ethnic minorities in work and as trade unionists? In Striking Women through the stories of the women at the heart of two important strikes – Grunwick in 1976-78 and Gate Gourmet in 2005 – we get a more complex view of the women activists that is grounded not just in their lives at work, but at home, and as part of the complexities of the UK labour market.

Central to this story are the women themselves. The authors interviewed five of the elderly Grunwick strikers, and twenty seven Punjabi women workers who were sacked by Gate Gourmet in 2005. They interviewed them in their own language of Hindi, “In the hope of bringing forth submerged accounts and hitherto unvoiced memories.”

The authors also interviewed senior officials in the TGWU (now Unite), observed Employment tribunals, and analysed the full judgements of the seventeen Employment Tribunal cases. The research gone into this book, and the analysis of these two disputes, must count for one of the most complex and complete examinations of the dynamics between trade unions and their members. It also shows how the massive changes in the political and economic realities of the period from the 1970s to the 2000s have undermined both workers and trade unions, and challenges present day trade union practices in representing workers.

Much has been written about the Grunwick strike, but in this book we actually get to hear from the women themselves, and most importantly as they look back at what was a defeat, the women are sanguine; “I felt great that I can do something. I was no longer scared of our community. Of what people will say.”

The Gate Gourmet dispute was at a different time, and led to different consequences for the women involved. By 2005 the women had been working in a unionised workplace for many years, but the anti-trade union legislation (which the Labour Government would not abandon) meant that it was not going to be a Grunwick mark 2, but this time with a happy ending.

But many of the issues were similar for the two groups of women workers. It was about feelings of injustice and a need for collective action to address these grievances. But the realities of 2005 meant that; “South Asian workers were once again subject to arbitrary management, treated as a “disposable” labour force and left unprotected by the wider labour movement.”

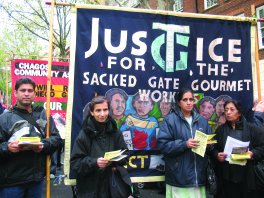

Gate Gourmet workers

The challenges for trade unions in 2018 are formidable, but unless they are prepared to challenge their own policies and practices as organisations, their relevance to groups such as black and ethnic minority groups is questionable. The Grunwick and Gate Gourmet strikers proved that South Asian women (like other ethnic groups) are prepared to organise collectively to oppose oppression at work, but the challenge to the trade unions is to prove that they can change their approach to these workers and adopt a more proactive approach to organising workers in an era of globalisation and restructuring.

Buy Striking Women, cost £18 (!!) here

Reblogged this on Anarchy by the Sea!.

Reblogged this on Industrial Workers of the World Dorset.